- Home

- Memories

- Scrapbook ▽

- Topics ▽

- People ▽

- Events

- Photos

- Site Map

- Timeline

Page added 22 September 2008

Return to Service Industry

Before the age of the railway, transporting people and goods across the country was a slow and tedious process. Even in Victorian times, people often walked long distances and some would think nothing of walking from Exeter to Plymouth, or further. Transporting goods overland was more tricky, especially for an industrial city like Exeter, with its production of woollen cloth. Exports could be sent by sea from the Quay or Topsham, while goods for London would sometimes be despatched in unreliable and slow coastal vessels; it could take several weeks for a vessel to beat up the Channel. Packhorse's were used to bring newly woven woollen cloth into Exeter from the looms in the surrounding country, and packhorse's were also used to transport goods from one town to another.

When the turnpike system became established, wheeled traffic increased and a system of stage-coaches for passengers, and waggons for goods appeared. The last of the long distance pack horses, run by William Iliffe from the Mermaid Inn, disappeared in 1739, as the major carriers adopted horse drawn waggons.

The largest of the carriers in the west country was Thomas Russell and Co., who took over and merged two already established carriers, Iliff, Partridge and Bird and William Avery to form one long haul carrier service in 1768. It is possible that Thomas Russell was already involved with William Avery. Initially the firm was a partnership between Russell and William Avery's widow Jane Avery. It had two main bases; the first was the Bear Inn, in Southgate Street, Exeter, and the terminus in London was the Bell Inn, Friday Street.

The Exeter terminus, the Bear Inn, had been used for packhorse carriers from early times, and was just one of many inns within Exeter that supported carrier services. William Iliffe was based at the Mermaid Inn off Preston Street and the Dolphin Inn, at the top of Preston Street was the terminus for several services from Ashburton, Okehampton, Totnes and Yeovil in 1729. Even with the demise of the long haul carrier services in the 1840's, many inns continued well into the 20th-Century with local carrier services to Devon towns.

Russell rented the Bear Inn at a cost of £213 and by 1798 he was running 300 horses. In 1800, he rebuilt the Bear to better suit his business when it became known as 'Russell's Waggon Office'. The terminus consisted of Russell's house overlooking the yard, warehouses, stables, granary, waggon stands, smiths' and wheelers' workshops, counting houses and other dwellings. Russell also owned a farm which provided provender (feed and bedding) and rest day pasture for the horses.

The route from Falmouth, through Exeter to London was divided into districts, with a proprietor in charge of operations in each area. The districts, in 1816, were Falmouth to Five Lanes (near Launceston) 12 miles, Five Lanes to Exeter 13 miles, Exeter to Dorchester 34½ miles, Dorchester to Worting 54½ miles and Worting to London at 53 miles. The mileage, was not the actual distance, but a mileage used to calculate the division of income for each district.

The Falmouth to Exeter route was sustained by shipments of bullion from Britain's overseas trade, and such an important service commanded a high rate.

Exeter was an important source of woollen cloth, and in the late 18th and early 19th Century, as exports to Europe were halted by the Napoleonic Wars, an alternative market in China, in return for tea was supplied by the East India Company from the London docks. The Banfill and Granger mills at Exwick provided much of this cloth and Thomas Russell wrote "Messrs Banfill Shute & Co are good friends of ours, and send all the goods they have to London and the road to us".

William Iliff introduced broad wheeled (9 inch) waggons in the 1750's, just before his business was taken over by Russells. Tolls for broad wheeled waggons were lower as they damaged the road surface less. Waggons were hauled by up to eight shire horses at a speed of two miles per hour, but hills would considerably reduce the speed to an average 1.6 miles per hour, when a ninth horse was added to the team. The first stage out of Exeter was to Redloft, near Honiton where either the team was rested before continuing to Dorchester, or sometimes it was changed for a return load to Exeter. Exeter district ran four teams of nine horses up to Dorchester, the 34 miles taking 25 hours.

The wooden waggons were huge and ungainly contraptions which towered over the horses. The rear wheels were 5 ft (1.52 m) in diameter, and the covering tarpaulin all of 12 feet (3.65 m) high. The bed of the waggon was 13 ft 2 inches (4 m) by 5 ft 3½ inches (1.6 m) wide. The whole unladen weight was 38 cwt (1,930 kg). In addition, the load would weigh as much as six tons in summer and perhaps five tons in winter.

The weather was a vital element in the efficiency of the service. It was quite common for consignments to be delayed by snow and in January 1819 a team was delayed by snow in Dorset. The next day it took thirteen horses to haul the load to Blandford. Mr Nichols, who ran that section, wrote "20 horses will not work a waggon from Blandford to Dorchester until the road is cleared going up the hill two miles west of Blandford." Although bullion was always at risk of theft, strangely, highway robbery was not the problem; the three cases of loss between 1816 and 1821 were at Falmouth or at overnight stops.

An important innovation in 1737, by a carrier on a Frome to London service, was the running of waggons continuously, day and night, with horses and waggoner's changed regularly - this faster service became known as flying waggons. The road speed of the service was no faster, but the time for Exeter to London was reduced, by Russell's, from seven days to 4½ days. However, by the 1820's this was too slow for some goods and customers, and light vans were introduced alongside the waggons in October 1821, when a speed of five miles an hour was attained. This allowed shipments of butter from the area between Exeter and Salisbury to compete with butter more local to London. They were not successful because they often returned with only a part load.

Thomas Russell retired in 1792 and his son Robert took over the business. On Robert's own retirement in 1816, a partnership of eight men was formed with Robert's son Thomas taking on the Exeter district. Changes were afoot as competition from the new steam packet services along the south coast emerged in the late 1820's. Previously, wind driven coasters could take weeks to reach London, and insurance costs were an additional expense. However, steam packets could not easily serve the intermediate stops along the route, and Russell's managed to retain much of the business, although their Falmouth route was severely affected by the loss of the bullion trade. Woollen cloth exports to China had ceased by the 1820's and more general goods were carried by Russells.

It was the coming of the railway tthat would finally end Russell's carrier service. In 1840, a line between London and Southampton opened, allowing connections with many of the packet boats that formerly docked at Falmouth. Most of the bullion trade was lost to the new service. Worse was to come when the Great Western Railway reached Bridgewater in 1841 and Taunton in 1843. The cost of transporting goods by rail was considerably cheaper, but it still need to be carried from the terminus to Exeter. A price abatement of 20% was offered to carriers who transported goods from the terminus onwards. The delivery time for London to Exeter was reduced to 30 hours, and there was a consequential reduction in the number and size of teams run by Russells.

The GWR had a clause that forbade carriers from sending small parcels for different customers in one large parcel, an early form of containerisation. Russells were caught doing exactly that, and their 20% abatement removed. In 1843 Robert Russell and Co closed while some of the other partners on the London route were bankrupted.

In 1845, the Bear Inn headquarters of Russell's was listed as "Steam Packet House late Russells Waggon Office South Street'. Pickfords, a northern carrier eventually took over the premises, which were closed and replaced by the Sacred Heart Church in 1885.

Sources: Road Transport Before the Railways by Dorian Gerhold and the Flying Post.

A

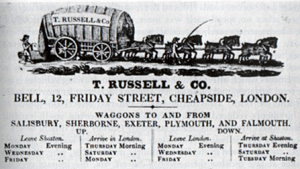

letter head for Russell's, showing a team of eight horses and waggon.

A

letter head for Russell's, showing a team of eight horses and waggon.

The Bear Inn, South Street in

1881.

The Bear Inn, South Street in

1881.

│ Top of Page │