- Home

- Memories

- Scrapbook ▽

- Topics ▽

- People ▽

- Events

- Photos

- Site Map

- Timeline

Page updated 3 May 2009

Written by David Cornforth and Anne Speight

Return to Industrial Exeter

There are two Bodley's associated with the city of Exeter; the first, Sir Thomas Bodley went on to found the world famous Bodlein Library in Oxford, while second was a family, rather than a single individual, who for 177 years ran one of the city's most successful and innovative iron foundries in the city.

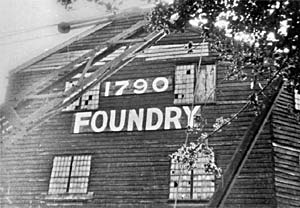

In 1786 a grocer by the name George Bodley died, passing on his entitlement as a freeman of the city, and his profession to his son, also named George (II). Not much is known about George Bodley (II), other than that his son, also confusingly named George (III) started an iron foundry in 1790, initially in the Westgate Quarter and soon after at Quay Place in what was then named City Road and later named Commercial Road. The young George meant business because he soon installed an independent melting unit for cast iron.

George (III) married Ann (possibly Parkin) and they

had 12 children. They were baptised as follows-

1784 George Norton -

St Petroc's

1786

Frederick – St Kerrian

1788 Mary Ann

1789 Charles

1791 Alfred

1793

Ann – St Mary Steps

1795 Caroline

1797 Louise

1799 Edwin

1802

William Canute

1805 Hurbert

1808 Sydney Octovus

In 1801 George (III) took out a patent with James Whitby a Cullompton tanner, and John Davis, for a bark mill, a piece of machinery that would grind bark for use in the tanning industry. Tanning was an extensive industry nationwide and it was estimated there were 5,500 tanners across the country; a good market for the machine. Even locally, there was a good, national market for a water driven machine and the city also had a healthy leather industry. The next year, George (III) patented the famous Bodley stove, a product that would sustain the foundry for many years, and then in 1816, a patent for a metalline engine was granted. George Bodley was into his stride and the business went from strength to strength.

Many of George (III)’s sons became involved in the family business. The eldest son George (IV) purchased castings and signed receipts for the foundry which appear in the original day book. Unfortunately George (IV) suffered ill health from 1812 and he died in 1819. Other son’s who took important roles in the business were Charles b1789, Alfred b1791 and William Canute b1802.

By 1835 the company was sometimes referred to as A & WC Bodley. George (III) had died and the company was being run by brothers, Alfred Bodley b1791 and William Canute Bodley b1802. In 1838 there was an amicable split when William Canute set up the West of England Foundry which was situated opposite the cattle market on land that is now occupied by Renslade House. Not only did the new foundry manufacture waterwheels and undertake other general foundry work, but William Canute took with him the right to manufacture the famous Bodley stove.

In the 1851 census, William Canute Bodley b1802 was living at Bonhay, St Edmunds parish, and described as an ironfounder, employing 14 men and 6 boys. Living with him was his wife Jane, and son Paul, along with nephew Christopher Mardon Taylor b1831, ironfounder.

Meanwhile, back in Commercial Road, Alfred b1791 ran the Bodley business. Alfred had married Mary Hutchins at St Thomas the Apostle in 1825 and they had 5 children – Alfred b1826, Mark b1828 (infant death?), William Canute 1832, Owen Arthur 1835 and Rhoda Stapleton 1837.

The 1851 census described Alfred b1791 as an ironfounder of Commercial Road employing 9 men. Living with him were his wife Mary, son Owen Arthur – an engineer and nephew Sidney T Bodley a pattern maker. Also living in the household was Frederick Henry Brook, an engineer.

In the 1851 census, Alfred Bodley b1826 was an engineer, who lived with his wife and young family, at 5 Lakes Buildings in Holy Trinity.

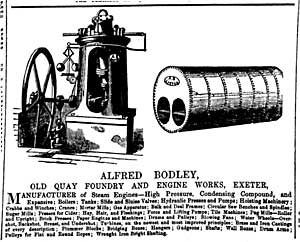

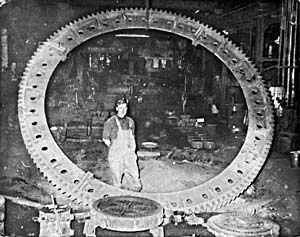

Bodley and Co. went from strength to strength manufacturing machine-tools, traction and steam engines, and making general castings. They also became specialists in manufacturing cast iron, machine moulded gear wheels, building up an impressive collection of finely carved, wooden moulds. They used machinery and techniques developed in Lancashire for the textile industry, adapting them for their own use.

Much specialist machinery was either purchased or designed and manufactured for their own use – mechanical cupola-charging machines, blast mains, fans, loam mills, cranes and drying ovens were installed in the mid 19th century. The largest machine tool, a lathe with extension chucking-pieces bearing the name on a plate of Alfred Bodley 1858, testifies to their own ingenuity.

In 1856, William Canute sold the West of England Foundry along with rights to the Bodley stove to Thomas Kerslake of the High Street. William Canute Bodley died in 1858.

In Liverpool, in 1855, William Canute Bodley b1832 married Mary Critchley. They made their home at Exeter and had 10 children although several died as infants.

For whatever reason, Alfred b1826 (II) who was works manager, quarrelled with his father and brothers (William Canute b1832 and Owen Arthur b1835) and as a result Alfred was removed from his father's will. In 1865, his father died at the age of 85 and some months later, Alfred (II) left the firm and went into partnership with Christopher Marden Taylor to form the other well known iron foundry Taylor and Bodley, at Northam's Foundry, Commercial Road. Within a stone's throw of each other, the two foundries would compete for business, trying to outdo their rival. However, the new partnership was also stormy, leading at times to an uneasy three way relationship between Christopher Taylor, Alfred Bodley and Bodley and Co.

In an attempt to maintain their legitimacy, William Canute b1832 and Owen Arthur b1835, had the letterhead of Bodley's re-worked to Bodley Bros. Sole Successors to the late Alfred Bodley.

In 1867 Owen Arthur Bodley b1835 married Louisa Rebecca Frost at Westminster, London, but they returned to Exeter and he continued involvement in the family firm.

Time rolled on, and in 1875 William Canute Bodley's wife died aged 41years. In 1876 he sold his shares to his brother Owen Arthur and within months William Canute Bodley was dead aged only 42.

Owen Arthur Bodley, William Henry Brook and Charles Ashford an accountant were charged with keeping William Canute's estate in trust until his youngest child was 21. Of the ten children produced by William Canute and his wife Mary, only Owen Henry b 1863 served his apprenticeship at Bodley's and stayed with them all his working life until his death sometime after the Second World War.

In 1878, after only 11 years of marriage, Owen Arthur Bodley was widowed when Louisa Rebecca died at the age of 47 in Exeter.

In the 1881 census Owen Arthur Bodley is described as 46 years, a widower, iron founder employing 50 men and boys. He was in lodgings at 43 Southern Hay, St Davids. The following year in Exeter, Owen Arthur was remarried to Manchester Alice McFarlane, who was 20 years his junior. They went on to have several children and in the 1891 census the family were living at 1 Mount Vernon, St Leonard's, Exeter.

It is unclear if the family freud with Alfred Bodley b1826 was ever settled. On the 1881 census Alfred Bodley b1826 is described as a mechanical engine maker, living at 69 Commercial Road with his wife and son Harold, also described as an engineer

The Bodley foundry continued to service the local mills, with new equipment and spare parts, and in 1891, a new and improved high breast undershot wheel was installed at Tracey Mill using Bodley castings installed by Michelburg Foundry at Honiton. The wheels for Cricklepit Mill were also cast at Bodley and Co; many gear wheels for the mills had cogs made of apple wood fixed into the cast iron wheel, as the wood did not require lubrication.

Calculations for gear cutting by the machine operator were made by chalking on the floor; chalk was provided as large lumps the size of a loaf of bread, and the operative would knock off convenient pieces. Chalk was also rubbed onto the metal of the job which was then rubbed off with the hand. A scriber, often a sharpened knitting needle, was then used to mark out the job to an accuracy of a 100th of an inch. Another product at this time, for export, were the large, steam heated, pans that were used for sugar production in the West Indies.

Owen Henry Bodley b 1863 married and had four children but only Colin Bodley joined the firm in 1905.. Owen Arthur had himself retired, ending his days in the family seat of Dunscombe, home of Sir Thomas Bodley, and closing the circle with his illustrious Elizabethan ancestor. Owen Arthur Bodley died in 1910, aged 75 years. The following year his grandson Colin left the family business. Owen Henry Bodley’s children – Colin, Elsie E, Alice Margaret and Rhoda took no further active part in the affairs of the foundry and the business was administered on behalf of Owen Henry Bodley’s children by the trustees, Campion the solicitors.

In the 1960's, machine tools that were well over 100 years old, all driven by a labyrinth of overhead belts and pulleys were still working hard. One lathe, which was driven by its own steam engine, had a base that was 25ft long with a big pit beneath to allow the turning of 8 metre or greater diameter wheels. Other machines were powered by a large, vertical steam-engine, which also ran the foundry cranes and coke fed cupola-charging mechanism. The works hooter on the roof was powered by the steam engine – it would sound at 7.55am for the start of the day and again at 8am when production commenced. If a worker was late he had to enter the works via the office gate to be checked in. Each worker carried a 40mm diameter brass disc with their works number stamped on the front; it was hung on a numbered hook on a board to indicate their presence, and registered by the Timey who kept the time book.

The two coke fed cupolas would take a day to melt down the scrap cast and pig iron; large fans would blast air into the furnace causing, on a cold winters day, bright red sparks to fly up like a firework display, from the chimneys that could be seen from all around Shilhay and St Thomas. When melted, the molten metal was tapped off and run into ladles to be poured into the greensand moulds on the floor. After the Second War, electricity replaced the steam engine to power the cranes and other equipment.

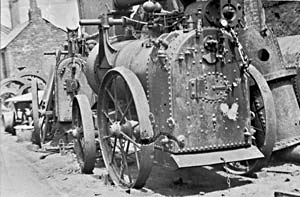

Before the advent of reliable petrol driven lorries, large castings were transported on a sort of low horse drawn, two wheeled chariot. They would be hauled over the Exe Bridge to the railway sidings at Haven Banks before transporting by train to the customer.

The last gearwheel castings were poured in March 1967 – the casting of a 140 tooth, 15ft diameter, 10 inch thick gear wheel for Russia was filmed by a TV crew. Two ladles of iron had to be poured – one of two-tons and one of three-tons.

Thousands of nineteenth-century wooden patterns made from mahogany and teak were stored over the office in the iron founder's town-house. Natural oils in the wood allowed them to be removed easily from the greensand that made the moulds.

Campions continued to administer the foundry until 1966 when Elsie Bodley, the last of the children died – the foundry was closed down the next year, 177 years after it was founded.

Much of the machinery was sent to the Science Museum in Kensington. Bodley and Co's collection of plans, photographs, working drawings, and other papers, from the founding in 1790 to 1959, were rescued from the Commercial Road premises and are stored in the Devon Records Office. Now, the place on Commercial Road that saw 177 years of industrial activity is given over to the Shilhay housing estate.

Sources: Martin Bodman's More Light on Bodley’s Old Quay Foundry, Memories of Cyril Brown collated in 1977 by the Exeter Industrial Archeaology Group, the Foundry Trade Journal March 30th 1967, Trewmans Exeter Flying Post and research undertaken by Mr C Coombe 1969. The history was partly re-written by Anne Speight following her detailed investigation of the genealogy of the Bodleys.

The proud 1790 sign

proclaims the founding year of Bodley and Co.

The proud 1790 sign

proclaims the founding year of Bodley and Co.

An advert from 1859.

An advert from 1859.

Scrap boilers and engines

outside the works.

Scrap boilers and engines

outside the works.

One of the giant gear

wheels.

One of the giant gear

wheels.

The foundry floor at Bodley

and Co.

The foundry floor at Bodley

and Co.

A Bodley wooden pattern

that

was used to make a sand mould to cast a gear wheel. Photographed

with the permission of

Aubone Braddon.

A Bodley wooden pattern

that

was used to make a sand mould to cast a gear wheel. Photographed

with the permission of

Aubone Braddon.

A gear wheel cast by

Bodleys, with apple

wood cogs, restored by Martin Watts at

Cricklepit Mill.

A gear wheel cast by

Bodleys, with apple

wood cogs, restored by Martin Watts at

Cricklepit Mill.

│ Top of Page │